Last week we did a thing – we announced The UnFundable Project, an opportunity for a Mecklenburg County nonprofit to receive a $10,000 allocation from Next Stage for a project “that would typically struggle to receive investment in a traditional grantmaking process.”

We are doing it as a celebration of our tenth anniversary as a company, and it’s pretty on-brand for us. We’ve spent a decade ‘stirring the pot’ for social impact, challenging our community to consider new and different ways of getting stuff done. It feels natural for us to use a milestone like this to shine a light on something we believe in wholeheartedly: trust-based philanthropy.

Today I’m going to give you some of the backstory on what inspires us to trust nonprofits and why we launched this initiative.

Dan Pallotta and ‘Uncharitable’

I’ve written over the years (here, here and here) about the important role Dan Pallotta has played in my formation as a consultant. Back in 2014, in the wake of his game-changing TED Talk, he came to the McGlohon Theater in Charlotte to inspire those of us lucky enough to be in the room. It was incredibly formative.

I had watched the talk countless times by that point. Indeed, it had been a part of what inspired the launch of Next Stage earlier that year. The message resonated so strongly – “the way we think about charity is dead wrong.” I had felt that way myself so often as a nonprofit practitioner, raising funding from individuals and institutions. It always felt sort of icky, inequitable, and just… off.

To be successful at fundraising is to hone in on the motivations of the individual being solicited, to align your fundraising message to the specific person making the charitable decision. It must resonate with them if it is going to move that person to action. All giving is ‘selfish’ in this way because it activates the pleasure receptors (what Penelope Burke calls warm-glow altruism) of feeling good about giving. A strong resource development professional is gifted at positioning the organization’s mission to align with the prospective donor’s ‘why’ – why they would willingly part with their money to support a nonprofit cause. And in this, ‘the customer is always right.’

Except, what about when the donor or funder is wrong? Is that even a thing? Can the person who wants to do good by donating money actually be a part of the problem?

According to Mr. Pallotta, absolutely. And his advocacy to get people to think differently about charitable giving quite literally changed the philanthropic industry. He challenged the ‘15% overhead myth’ and got Guidestar, BBB and Charity Navigator to change how they ranked nonprofits against the false premise that such financial ratios are a priority indicator of organizational performance.

If you have an interest in learning more about his work, his founding of the Charity Defense Council, and his ongoing efforts to build a social movement around challenging norms, he has a new movie coming out called Uncharitable, based on his book of the same name. Though a local screening for next week is sold out, I have a feeling it will be coming to streaming services soon.

The Broken System is Still Broken

So, clearly, Mr. Pallotta solved philanthropy and it’s perfect now, right? Rejoice!

Of course not.

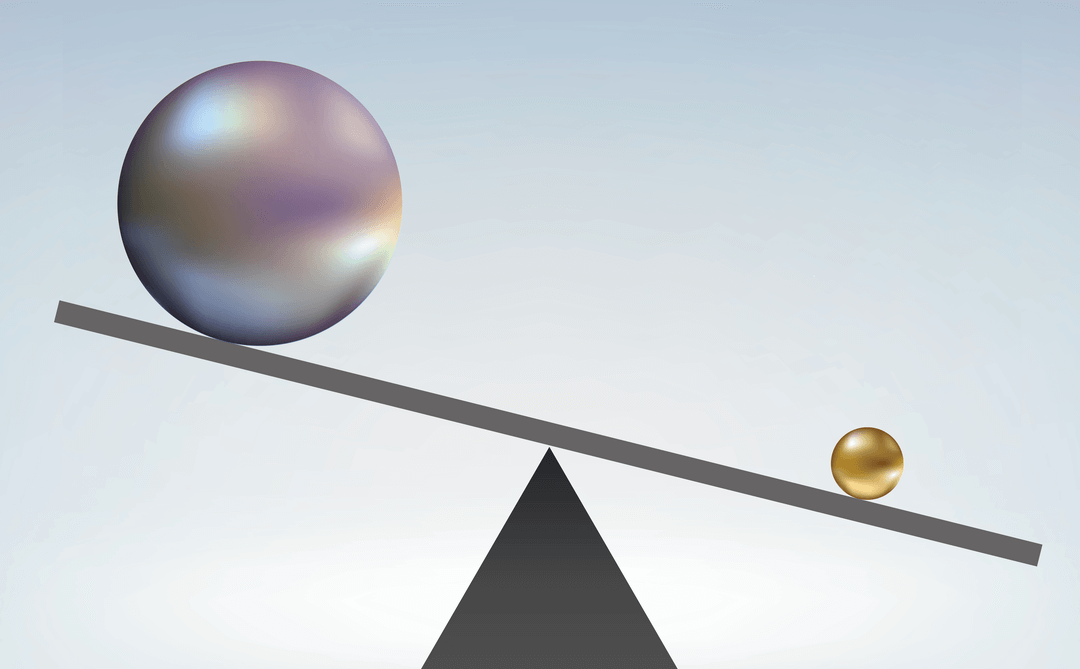

While the overhead myth was a particularly important dragon to slay, it was always a symptom of a much more insidious problem – a central lack of trust. Nonprofits and the people who support them too often have a delta of trust in both directions.

As I’ve shared in many talks, the root of this is generational and historical. The WWII Silent Generation was generally a very trusting generation, apt to support causes that met needs at both the local and global levels. That led to a rise in nefarious charities that took advantage of their generosity. The Baby Boomer generation, which had lost faith in institutions following the Nixon administration and the Vietnam era, began to conflate government and the nonprofit sector. It was Boomers who first introduced the overhead myth, the concept of ‘duplicating service,’ and generally aspired to see much greater accountability for nonprofits.

The idea of ‘holding nonprofits accountable’ continues to inform most grantmaking activities. In addition to an in-depth application for support, an organization must lay bare its entire financial self to assure a grantmaker of no ‘funny business.’ After the grant is made, reports must be submitted that demonstrate impact in predetermined formats selected by the grantmaker meant to create an apples-to-apple comparison across the gift-giving portfolio – whether it fits the organization’s services or not.

These expectations set forth by institutional grantmakers have a trickle-down effect on individual donors at all levels, who often harbor a mistrust of the very organizations they charitably support. I have personally heard all kinds of ridiculousness sitting across from well-intentioned people about what they think is happening back at the nonprofit’s office once their check is cashed.

For its part, nonprofits have a healthy lack of trust for these individuals and institutions as well. Wouldn’t you? Who wants to be treated like a child? It is difficult to think of someone as a partner in the work when there is a central lack of trust in decision-making. This unequal relationship – complete with the ‘funder voice’ talking down to the grant seeker – is far too common, despite Mr. Pallotta’s best efforts to date.

The Rise of Trust-Based Philanthropy

Trust-based philanthropy got its start a little more than a decade ago at The Whitman Institute, a San Francisco-based grantmaking institution that has since ended operations. Following the financial crash of 2009, the funder elected to escalate its giving rather than pull back as many others were. They focused on multi-year, unrestricted giving and grant check-ins that were heavy on relationship-building and lighter on paperwork and reporting.

It was an approach to grantmaking that inspired others, and soon the institute’s leadership was hosting formal and informal discussions about how it approached trusting the nonprofits it elected to support. In January 2020, it led to the founding of the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project. COVID hit a few months later, and the rest is history.

I won’t attempt to restate all the richness on the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project’s website. They focus on working with grantmakers to transform their culture, structures, practices and leadership. It’s an amazing framework and I’m excited that Charlotte-based institutions like Foundation For The Carolinas and Women’s Impact Fund have hosted conversations about it.

But as many of us know in the nonprofit space, institutional funders make up a modest (though significant) percentage of overall philanthropy in America. The vast majority of contributed dollars (like more than 80% of charitable giving) come from individual donors.

Unfortunately, individual donors don’t typically view themselves as needing professional development to be better donors. In fact, most nonprofits are unwilling to take their donors to task for the wrongheaded things they think for fear of losing their support. Instead, the ‘toxic donor’ is met with forced smiles and eye-rolls when they aren’t looking.

That’s why Mr. Pallotta’s film is so important, and hopefully the same sort of energy behind Next Stage’s UnFundable Project. In partnering with The Charlotte Ledger, we hope to get the word out about the importance of trusting nonprofits.

Here’s why I think you should lead with trust when making contributions to nonprofits:

Oversight by the Board of Directors

Even if you didn’t trust the Executive Director or Gift Officer asking you to support the organization (which begs the question – why?), nonprofits have a built-in accountability structure in the board of directors. Many unpaid volunteers throughout our community take on fiscal responsibility for our nonprofit organizations through their service as members of a nonprofit’s board of directors – it’s an amazing thing!

While they aren’t typically sitting with the Executive Director every day, watching every move, they shouldn’t have to. They are responsible for hiring that person and thus tend to have trust built with the administrative leader. While some boards fall down on their charge, in my professional capacity, I have seen hundreds of boards and have found them to be mostly competent and diligent in their oversight.

Experience and Proximity

Nonprofit organizations are often led by people with much more experience in the field than the person making a charitable gift. Just as I am not in the habit of micromanaging service providers in fields outside of my understanding, so too do I tend to trust the nonprofit leader who lives and breathes the organization’s mission statement. They have earned that respect, whether through academic credentials, on-the-job experience or lived experience.

Beyond that, the nonprofit is closest to the issues and causes we are trying to address. They are often ‘boots on the ground’ in the community, listening to the needs of people and experiencing the conditions informing success first-hand. Funders and donors typically have little or none of that first-hand experience. And if they do, it is not as contemporary as the person sitting across the table who does this work every. dang. day.

One Bad Apple Doesn’t Spoil the Barrel

Those who champion stronger controls on nonprofits are quick to point out examples of negligence leading to bad outcomes. I am not saying that all nonprofits are doing what they are supposed to be doing. While bad decision-making is far more likely a function of lack of understanding than management malfeasance, that sort of thing definitely exists. I’ve seen it.

But just because one organization did something wrong doesn’t mean that wrongdoing is just under the surface of every nonprofit, just waiting to burst forth when everyone’s guard is down. You are far more likely to find wrongdoing inside the walls of the private sector where we invest our life savings than in the community-based nonprofit down the street. And it is time we acknowledged this out loud as people connected to the nonprofit sector.

So that’s what is behind The UnFundable Project – a desire to highlight the importance of trusting nonprofits and the people who make them go. They are most often tireless crusaders for people in lesser positions. And in this, we see our role as championing them when their own speaking out could cause a backlash.

It is time we changed hearts and minds about the role of nonprofits in society. Help us spread the word – tell a nonprofit about our grant, and then tell a neighbor why we’re doing it.